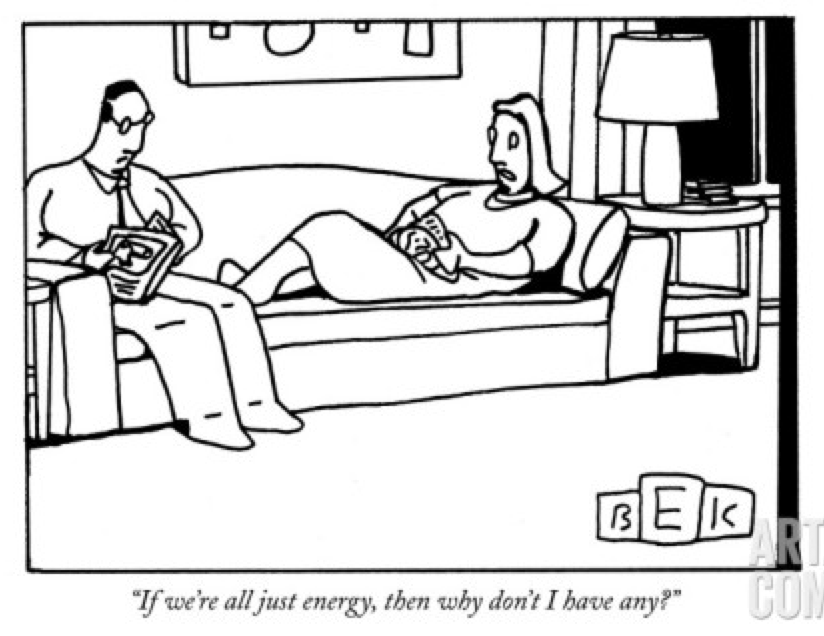

We tend to think about our energy level like the money we have in the bank. You wake up in the morning, look in your energetic wallet and say, "I've got a lot of energy today" or "Man, I need 7 cups of coffee."

Or, to put it another way, thanks to this New Yorker cartoon:

In qigong, we think about "having energy" a little bit differently. Often, it's not just how much or how little, but how well is your energy circulating?

Good energetic circulation gives you a feeling of "more," while stagnant or stuck energy feels draining.

Since this is such a different concept than most of us have, I've often wondered about where these two ideas came from and where these two ways of seeing the world split. In this post, I'm not going to give you a deeply researched exploration of the origins of the Taoist understanding of the world. I'll let our practices stand as of evidence of that.

Instead, I want to share with you some of the writings of 20th century Western philosopher Hans Jonas. He wrote about the phenomenology of life and in his descriptions of biological processes, we get a really interesting connection to what many qigong practitioners come to realize: we have a fundamental need to circulate chi.

In The Phenomenon of Life, Jonas is trying to reconcile the simplest forms of life with higher thought and our human experience of the mind. He tries to place them on a continuum and asks which one is for the sake of the other.

Whatever the answer, one aspect of the ascending scale is that in its stages the "mirroring" of the world becomes ever more distinct and self-rewarding, beginning with the most obscure sensation somewhere on the lowest rungs of animality, even with the most elementary stimulation of organic irritability as such, in which somehow already otherness, world, and object are germinally "experienced," that is, made subjective, and responded to (p.3).

My personal theory on the origins of qigong is that those early Taoists went exploring.

They sat or stood in postures and listened, both inside themselves and to the natural world. As they got quieter and more perceptive, the heard the echoes of Jonas' "most obscure sensation." The irritability that Jonas describes set them up against the world outside and framed their inner worlds.

That irritability is the same itch you feel when you know you need to get your chi moving, circulating through you and passing back and forth between you, the natural world around you and the other people you interact with.

When things are flowing, in and out, up and down, towards and away, we feel good: connected to something outside ourselves but at the same time internally unified and integrated.

Just like eating, breathing, and sleeping, circulating energy is a natural cycle that we can refine, enhance, and enjoy, but we need to pay attention to it on an ongoing, continuous basis to be healthy and feel whole.

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email