In this post, I’m going to tell you what I learned doing a series of Rails security exercises developed by Bearclaw, a Rails security consultancy.

Before I go into the exercises, though, I want to send a huge thank you to Ali Najaf, founder of Bearclaw. What I’ve learned here is due to the thoughtfulness of the exercises he’s put together and his willingness to try something new by sharing them with me. Normally these exercises are part of a workshop he leads in person.

If you find anything in this article useful or interesting, please reach out to him and send your thanks!

What’s in a URL?

One of the first things I remember about learning Rails was how declarative the URL structure is for explaining the context of the resource you are viewing. For example, all your users will be viewable on the /users page. A single user is viewable on the /users/7 page.

We even had a running joke at my last job that none of the developers actually knew where anything was in the UI. Instead, we would all just type in URLs for whatever we wanted to view, because we knew which controllers and actions we were working on.

Rails relies heavily on the convention that an HTTP action should match a standard URL structure and a standard place in the code where that action is handled. For example, from the Rails routing guide:

- a GET request to

/photosmaps to thephotos#indexcontroller action and you can expect a list of all photos - a GET request to

/photos/newmaps to thephotos#newcontroller action and you can expect to land on a form for creating a new photo - a POST request to

/photosmaps to thephotos#createcontroller action and it will create a new photo - a GET request to

/photos/:idmaps to thephotos#showcontroller action and you would expect that action to display a specific photo

Of course, for a web framework to work at all, there has to be a concept of ‘routing’ where web requests are mapped to program logic. If you know the Rails conventions for this mapping, when you start up an unfamiliar Rails app, you can often take a pretty good tour of the app, just by making some assumptions about the URLs you would expect to find.

While I used to think of this as convenience and convention, now I see the flipside of this standardization: the more you follow the common patterns, the more I already know about the internals of your application.

In fact, the first exercise in this series drives home the point. Looking for “typical” Rails routes was all it took to exploit the app.

Can You Keep a Secret?

The goal of each of the exercises in the series is to find a “secret” – a random based64 encoded string – that’s displayed somewhere in the application. In each exercise, you have to compromise a different security mechanism to get access to the secret.

Each exercise is its own small Rails app, so to get started, there’s a little set up to run it locally. Then, when you view it in the browser, you’re prompted to log in or create an account.

For the first exercise, after you log in, there’s a navigation link to “Your Secret.” Clicking on that, guess what the URL is? Just like the photo example above, it’s the straightforward Rails URL, so if you go to /secrets/39, you’re going to see the resource with that id.

From there, all you have to do is match up the secret to the specific user secret (whose name is displayed on the secret page) that you’re after in the exercise. A little light scripting with something like Mechanize lets you test a whole range of secret ids and confirm you are on the correct user’s page. And, that’s it, the app is compromised!

Now, hang on, I know what you’re probably thinking. This is not a real Rails vulnerability and no one would be stupid enough to let all their user data sit out at exposed endpoints with no authorization checks. Fair point.

But that’s what is so cool about this series….You feel like you’re interacting with a real application, but the exercises are contrived in a way to make each attack vector clear.

In this case, the app had a glaring weakness that forced you to think through URL manipulation to expose data. It was a warm-up, graded ‘easy’ — there are more complex ones, all the way up to ‘diabolical’!

Next!

Expanding on the notion that the URL reveals information about the system resources, the next exercise exposes a password reset field on the /users/:id/edit page. Whoops!

Not only can you get a sense for how many user records are in the database, but if you visited all the edit pages one-by-one, you could easily set all the user passwords to whatever you liked.

Since I knew the id of the user I had just created, a simple for loop – from 1 to my user id – was all it took to set everyone’s password to ‘password’. Then I could log in as the user whose information I was after.

Again, is this typically how password resets work? Of course not!

But due to the design of the exercise, I learned that sometimes you can get at a particular target by compromosing all the data.

Time for Some Self-Promotion

The set up for the next exercise hinted that managers had access to special information that regular users did not. When I thought about Rails apps I had worked on in the past, one of the simplest contrivances to separate special users from regular users was to set admin: true on a user account.

Often, the admin-ing of a user is done through a superuser set-up script or directly in the database, which I didn’t have access to here. Ultimately, though, the admin flag is just an attribute of the user, so if I could find a way to add in additional info about my user, maybe I could promote myself to admin?

Yes, out-of-the-box Rails will guard against accepting user input on any model attribute via whitelisting what is changeable for any given action, but maybe…

It turned out, in this vulnerable little app, I could happily suggest attributes to edit on my own user edit page, beyond name and email. When I submited the form on /users/:id/edit, I could send along some HTML that added one more form field, setting user['admin'] to true. The controller action, it turned out, did not whitelist which attributes it would accept in the edit action, and I became an admin.

In this particular challenge, I had to apply the same concept again, weaving my way through other attributes and associations, until I was the admin for a particular group of users, one of which had the info that I needed to solve the challenge.

Each time, the changes were a combination of iterating through resource ids as we did in the previous challenges and altering the information with additional HTML embedded in the user edit form.

Very interesting to note here that editing the form HTML can be done easily in the browser, with all other authentication mechanisms already in place. In other words, I logged in as a valid user, verified by a session in the application, and sent requests that would have otherwise followed all the “rules” of the app – I just happened to throw in some extra data.

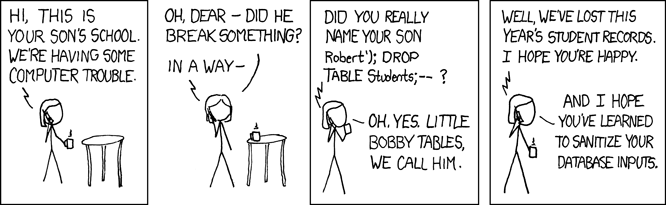

Little Bobby Tables Learns Javascript

This next one really stoked the growing feeling I had that I was getting away with something devious and delicious all at the same time.

Now, we weren’t blowing up a database with SQL injection, but it was a similar idea:

I learned that any time you let a user enter unescaped HTML, you run the risk of letting malicious code into your application. I mean, I guess I knew that in theory, but in this exercise, I learned how to actually do it…and it felt good!

Here’s how the attack could work.

If there is a field in a form somewhere that accepts any HTML tags, a user could enter something like <h1>This is an H1 you were not expecting!</h1> and now, anywhere that the field is displayed, whoever is viewing it will have a nice big H1 in the middle of their page.

So far, that doesn’t seem so bad…but the fact that one user can create input that shows up for another user in this way is critical to understanding the problem.

Next, instead of page styling, let’s throw in some javascript. If the input isn’t sanitized, meaning we haven’t been explicit about which tags are allowed or not allowed from users, or we’ve outright converted the tags into harmless strings, then something like <script>alert('whoops, this should never happen!');</script> could totally happen.

Now, a little alert isn’t going to hurt anybody, but remember how any other user will see whatever we put into that field? Since we can include a <script> tag, we can use javascript to manipulate the page and scrape anything else that’s on other user’s page, like account information or user data.

Here’s the part that I found extra devious: How do we retrieve the information we maliciously scrape from another user’s page?

See that XKCD comic a couple of paragraphs up? Do you know where I got it? I mean the actual embedded image? Right here:

<img src="http://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/exploits_of_a_mom.png">

I’m not hosting that image. I’m requesting it from xkcd.com. And if I owned xkcd.com, I would look in my server logs and see a request come in for:

/comics/exploits_of_a_mom.png

I would also see a request come in for:

/comics/exploits_of_a_mom.png?foo=bar

or:

/comics/exploits_of_a_mom.png?secret-user-data=here&is&the&account&balance

In other words, it’s easy to request the image resource itself or any other valid url at the domain, plus any other random data stuffed into the querystring params.

When you roll all this up into some evil user input, the script tag will:

- Scrape some data on a page where I expect the input to be displayed.

- Create a fake

<img>tag to be inserted into the DOM - Set the source of the

<img>as a URL that I control, with a querystring param that includes the scraped data

Now, when someone renders the page with my input in place, I will steal their data and ship it off to my server. So evil! So clever!

Fear Not…Or Do?

As I’ve tried to point out several times, following Rails conventions pretty much ensures you are protected from accidentally allowing any of these exploits to slip into your app. This is not an article about Rails vulnerabilities.

Instead, I’m hoping you’ll ponder this: a web application is valuable because it can gather data and then display it. A web framework is easy to use and maintain as a developer because it follows strong conventions.

Doing these Rails security exercises has flipped these tenets around for me.

Now it feels like a web application is dangerous because it can gather data and then display it. A web framework is easy interrogate and exploit because it follows strong conventions.

I don’t quite know how to reconcile these perspectives, but having gone through these exercises, I’m sure I will now be a little more cautious, a little more skeptical, and hopefully, a little safer as a developer.

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email