Lower back pain can be a frustrating experience whose source may be hard to pin down and whose remedy may seem elusive. I hope that as you read through this article, you can start to understand the nature of pain a little differently. I'll also show you some tai chi concepts that can help you unravel your lower back pain, and more importantly, how to search for a solution for your individual situation.

How Do You Define Pain?

If you want to fix something, you have to know what it is, right? When I ask most people to define pain, I usually hear "Pain hurts" or "Pain means I'm injured". If you think pain means you're injured, and you've tried every possible thing to fix yourself, then you're setting yourself up for some serious frustration.

Take a look at how the International Society for the Study of Pain defines pain:

An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.

Do you see an "equals" sign between pain and injury? Do you even see injury as a necessary part of what creates the experience of pain? The researchers at the forefront of pain science understand that pain is a lot more complex than "I'm broken therefore I hurt". So let's break down this complexity.

First off we have "unpleasant sensory and emotional experience". That's how I feel about my alarm clock when it goes off in the morning. And that's how you should think about the experience of pain. Your alarm clock is designed to jolt you out of sleep and into action, just like the pain experience. "Hey, you, do something different". In the case of your alarm clock, it's because you have to get up and get to work, so why does your body set off an alarm in the case of pain?

Well, let's look at part 2: because of actual or potential tissue damage. Actual or potential. Does that mean you're already broken? Maybe. But pain can also be an early warning signal, alerting you to a threat, before there is damage.

The "associated" part is interesting too, because, especially in chronic pain situations, you can't dismiss associations people may have on a lot of different levels -- not just mechanical, but emotional as well. Context and association influence the pain experience. The classic example in this case is a 1991 study of Boeing employees, that showed a strong correlation between back pain and job dissatisfaction. Researchers tried to control for physical and genetic factors and found that the emotional state of employees, both on the job and in their home lives, had a huge impact on whether they reported back pain. Lead researcher Dr. Stanley Bigos, said "people don't hurt as much if they have something better to do".

My personal pet peeve: I just need to point out here that people tend to take the experiential component of pain too far, and write off others in pain by saying "It's all in your head". Yes, actually, if you look at it from a neurological point of view, that's largely true. But I also think it's an incredible disservice to dismiss the experience of pain for that reason. It's a gross oversimplification. We'll do much better to say, "Let's decode this signal, find out what the signal means, or whether the signaling mechanism itself may even be broken, and get you out of pain.

How Tai Chi Helps Treat Lower Back Pain

The Z Health mantra is pain is all about "signals and interpretation". If you want to get out of pain, you have to understand what the pain signals are trying to tell you and one way to do that is to build up greater context for interpreting them. This is where Tai Chi comes in.

The reason that Tai Chi is done in slow motion is largely so that you can take the time to feel your way through your own body.

When you slow down, and start feeling different moving parts, your brain starts "mapping" your body differently, that is, it devotes more space to each individual part, instead of lumping things together. Why that matters for movement-related pain is that poor differentiation in your movement map means that the wrong body parts are being pulled and moved at the wrong times. Eventually, if your lower back is doing the job your hip joint was designed to do, and you can't tell the difference, you are going to tweak it. It's a bit like using a screwdriver to pound in nails, or trying to saw wood with a hammer.

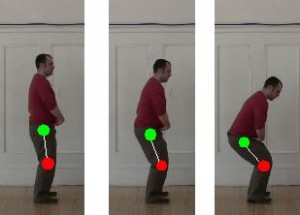

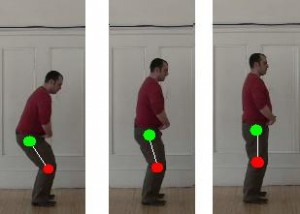

Notice in the video above, all the twisting and turning of the body is done from the hip joints, while the spine stays straight. Tai Chi does this to create very specific internal pressures in more advanced practices, but at the beginning level, it's a great way to ease up on torquing the lower back, and re-learn how to move from the hips. Before you get into the turning movements, though, you should try this more straightforward (haha!) squatting exercise:

The clearer the rotating sensation is in the ball and socket joint of the hip, the better. It should be equally clear on the way up:

As you learn more tai chi, the pivots, shifts, and turns get more complex, which opens the hips up to a much greater degree. Most of the students I teach, who come in with sedentary 9-5 jobs have completely frozen hips, and they move in a way that substitutes incorrect spinal movement for proper hip movement. When you begin to relearn the correct hip movement, you don't have to tell yourself "stopping moving your spine wrong". Instead, with more information to draw on, your body naturally corrects.

All of the moving parts, your bones, joints, tendons, and ligaments are like the factory workers at Boeing. They "don't hurt as much if they have something better to do".

For the Astute Reader

Now, some of you reading this will probably say, "hey, you gave us this whole rap at the beginning that pain isn't about tissue damage, it's about signaling, then you proceed to give us a mechanical solution to lower back pain in the tai chi example. What gives?" Good question.

We're still operating under the assumption that the source of the pain is not the cause of the pain. This is a pretty radical shift when you think about a typical response to back pain: stretch it out or get surgery. On a mechanical level, you need to understand individual body parts in the context of all the other moving parts in the system. The site of actual tissue damage from repetitive movement only exposes the weak point in the system. "Frozen hips" causing knee and back pain is the clearest example.

In a broader sense, I urge you to make the shift from single-point to contextual thinking about pain. That's the whole point of the IASP definition above. Yes, there may be mechanical factors, but there may also be emotional factors or other sensory factors that contribute to the pain experience. Your pain experience is a highly individual combination of all of them and ultimately, you have to investigate it for yourself. At Brookline Tai Chi, we get more and more students referred by physicians for balance and chronic pain issues. The ones who walk in the door thinking that they'll take a "dose of tai chi" like a pill don't last very long. On the other hand, the ones who get excited about exploring tai chi start to develop more and more powerful tools for addressing their chronic conditions. How do you separate the educational component from the therapeutic component in this case? The more we understand pain, the more you realize you don't have to.

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email